By HILLIARD HARPER

Los Angeles Times

DEC. 2, 198812 AM

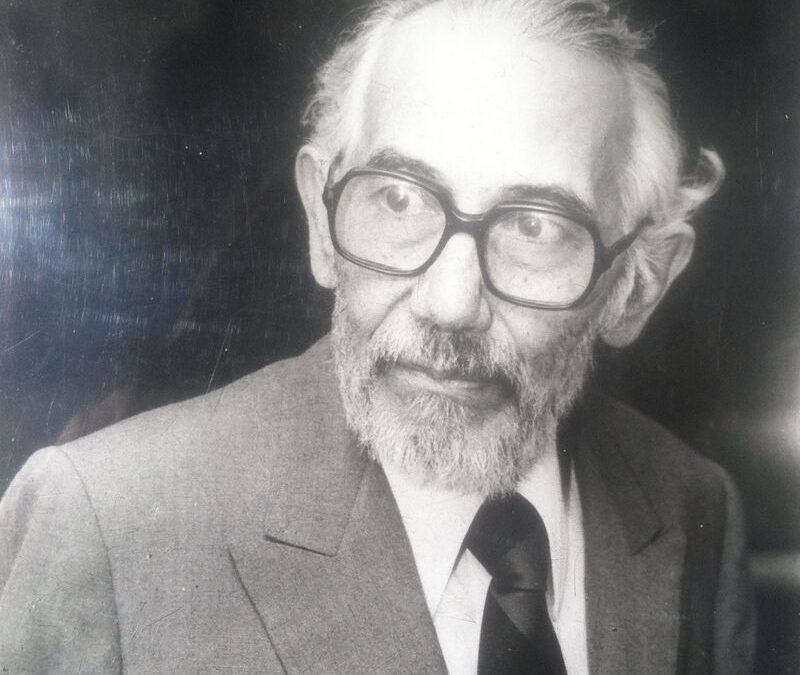

Guillermo Acevedo was a courtly, self-effacing man, an artist whose sardonic sense of humor recognized life’s hypocrisies, including the irony of his own life.

A skilled draftsman who trained as an illustrator, he struggled between the need to support his wife and three children and the inner artistic urgings to leave illustration behind and be more creative. The realities of life put him in conflict with his basic nature.

“My life is pure observation,” he told a Times writer in 1986. “I am a natural observer. . . . You look with care, not with love. It is impersonal.”

Call him a pragmatic observer, who learned to deftly wed a sense of social awareness to an instinct for what would sell. Acevedo, who died of cancer at the age of 68 in October, identified with the underdog–whether it was native Americans shunted aside onto reservations, endangered Victorian houses or tuna boats that ironically enough have begun to disappear from San Diego Bay.

“Life Achievement: Works by Guillermo Acevedo,” at the Acevedo Art Gallery Internacional, 4010 Goldfinch, shows how he sought to balance his social and familial commitments. Organized by his son and fellow artist, Mario Acevedo Torero, the exhibit runs today through Dec. 31.

Acevedo will also be honored this weekend at San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square. “Indian Family Christmas,” a three-day arts fare featuring 10 of the top living North American Indian artists, is dedicated to Acevedo and his family.

“I don’t know if he was in the Indian community, but he was of the Indian community,” said Rob Baker, marketing director of the Corporation for American Indian Development in San Francisco. “There’s something about the (Indian) culture that promotes the growth of families. Here’s a guy who embodied all the things we strive for in his family.”

Acevedo, who traced his ancestry to the Incas through the Quechua tribe of South America, was born in Peru. At the age of 38, he worked his way to San Diego on a tuna boat in 1958 and brought his family along afterward.

He soon was using his training as a commercial artist as a sign painter and worked briefly as an illustrator with KGTV, Channel 10. He began taking his drawings of San Diego scenes to weekend art marts in Balboa Park where found he could make as much money as he did during the week.

A facile artist, Acevedo could whip off a complete pen sketch of an 80-year-old house complete with gingerbread ornamentation in a matter of minutes. In the 1960s, his works soon found their way into fund-raising events by the Save Our Heritage Organization.

“I remember once that Acevedo did a drawing of the Santa Fe Depot,” said Harry Evans, a founding board member of SOHO and a former president of the San Diego Historical Society. SOHO sold a number of prints of the drawing, which “had a bearing on persuading Santa Fe not to tear the building down,” Evans said. “Actually what he did was create some enthusiasm and concern for these buildings.”

But it was Acevedo’s “discovery” of the Navajos in the late 1960s, his son said, that allowed him to find himself.

“He had been searching for himself,” Mario Torero said. “In the faces of the Indians, he could see the human race that he couldn’t see elsewhere.”

Acevedo’s trademark work became pencil portraits of ancient, craggy-faced Indians, with a blush of hand-colored turquoise ring or necklace setting off the basic black and white image.

But even these troubled the artist, said fellow artist Salvador Roberto Torres.

“He would be disgusted with the (commercial) aspect of these artworks,” Torres said. “But he had to support his family. Yes, he could see hypocrisy in life, but he first saw it in himself.”

Acevedo included his sense of human irony even in the images of the wizened Indians. In juxtaposing the lined faces with an unexpected touch of luxurious turquoise jewelry or drawing a wrinkled hand reaching out to a brilliant paisley butterfly, he captured the delicacy and contradictions of life.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE LINK BELOW

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-12-02-ca-1217-story.html